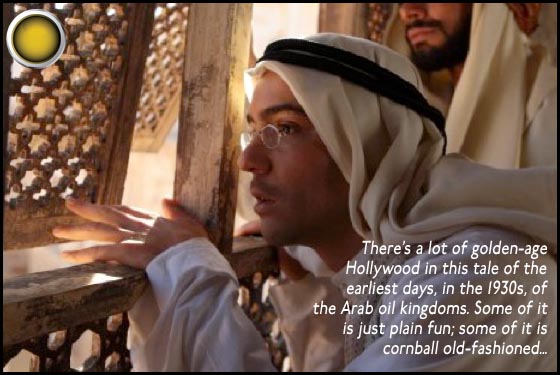

There’s a lot of golden-age Hollywood in this tale of the earliest days, in the 1930s, of the Arab oil kingdoms. Some of it is just plain fun: sweeping desert vistas and epically staged battles on horseback. Some of it is cornball old-fashioned, like the fact that of the four main Arab characters, one is played by a Spaniard (Antonio Banderas, loving every minute of his turn as the first oil sheik), one by an Anglo-Italian (an underutilized Mark Strong), one by an Indian (Freida Pinto, also given short shrift), and only one by an actual Arab (French-born Tahar Rahim, unrecognizable from A Prophet (Un prophète) and the best reason to see this). Screenwriter Menno Meyjes, working from the novel The Arab, Hans Ruesch [Amazon U.S.] [Amazon Canada] [Amazon U.K.], brings hints of Indiana Jones cheek — not unexpectedly: he contributed to the sublime Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade — to get the story rolling: Young Prince Auda (Rahim) is sent by his father Sultan Amar (Strong: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) to be a hostage of Emir Nesib (Banderas: Haywire) to ensure the peace between them after a war over disputed lands. He’s a “hostage” in the sense of “adopted son,” not “throw him in the dungeon,” and Auda grows up happy, his bookishness indulged, his affection for Nesib’s daughter, Princess Leyla (Pinto: Rise of the Planet of the Apes) tolerated. All is well, until oil is discovered in the disputed lands, and though Amar and Nesib had agreed that neither would profit from this domain, Nesib gets in bed with Houston, and the wells start to blossom. Alas, all the juicy mojo that had been building — Auda’s torn loyalties; the undercurrent of conflicting desires over maintaining a traditional way of life versus using the oil money to move the kingdoms into the 20th century; the impossibility of a truly romantic relationship when one party is kept a virtual prisoner (that would be Leyla, more constricted as a daughter than Auda is as a hostage) — dissolves as military strategizing in the new war between Amar and Nesib takes over the narrative, and director Jean-Jacques Annaud (Two Brothers) gives up on keeping the focus as personal as its been. “Is there a greater curse than to be a poor king?” Nesib asks sadly early on. Yes: letting a potentially great story slide away into mediocrity.