Sinners is a movie to make you remember why you fell in love with movies. A movie to make you fall in love with movies all over again, if, say, perhaps *ahem*, The Movies have gotten infested by IP contractual obligations and it feels like there’s nary an original story or authentic voice to be found on the big screen lately, and everything goes straight to streaming anyway so why even bother making the trip out to a big screen.

But here comes writer-director Ryan Coogler with his cinematic event, an unmissable howl of a passion project that is big and bold, messy and magnificent, and wildly primal. Sinners is fueled by pain and rage, but also throbbing with community and family, with love and sex and joy. It is infused with all sorts of magic. It is set almost a century ago, but it is very much of this particular moment. It is exactly the movie we needed right now, in so many ways, a pushback to the racism and reactionarism that is engulfing us.

This is a sumptuously textured movie in which you feel the many layers at work even if you don’t understand — or even grasp — all of them. Many audience members will not, because Sinners is deeply steeped in African-American history and culture, which is ignored at best, sidelined on the regular, and denigrated at worst in the larger American mainstream. I won’t pretend that I am able to appreciate all of it in its many depths, though I’m keen to learn more. But it is that profound richness that elevates Sinners above 90 percent of popcorn blockbusters.

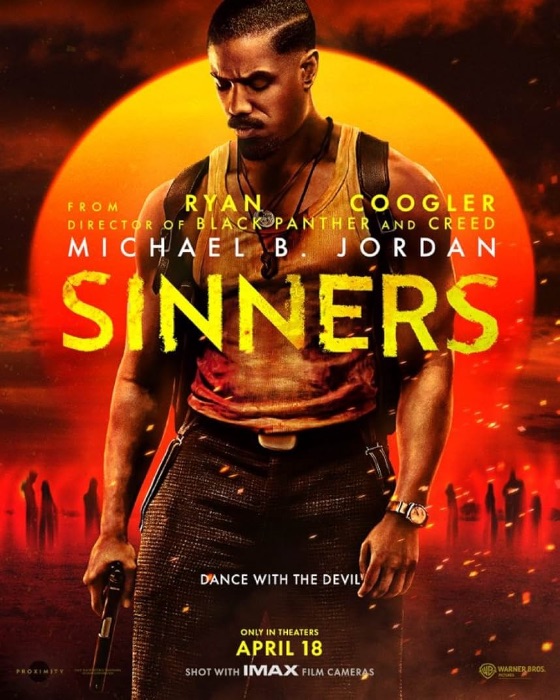

Which is what this is! This is the pulpy tale of two brothers from the Mississippi Delta who ran away to Al Capone’s Chicago but have now returned home. It is October 1932, and they’ve been gone for seven years, which is a very witchy number. Not that anyone notes that… it’s part of the unspoken magic coursing through Sinners, like the snake they kill right as their odyssey here begins. The brothers are Smoke and Stack, aka the Smokestack twins (both played by Michael B. Jordan [Just Mercy, Creed II], Coogler’s regular leading man, his De Niro to the director’s Scorsese), and they have brought with them literal bags of money and a literal truckload of Italian wine and Irish beer; the very-much-spoken suggestion is that they have stolen all of this from the rival Windy City mobs and are now, in fact, on the run from them. Their plan is to set themselves up with their own juke joint, a sort of informal nightclub, no whites allowed.

The film takes place over the course of a single day and night, as the brothers set up their establishment in an old barn purchased just that morning, rally local friends and family to help them prepare to feed and entertain their hoped-for customers, spread the word, and finally open for business as the sun goes down. It’s going great at first, until… Well, Coogler has, up to this point, about an hour in, been masterfully weaving his opulent but only supernaturally tinged dramatic tapestry, so rooted in this particular place and time, so full of down-to-earth Jim Crow–era horrors (the Klan, prison chain gangs, tales of lynchings), and so engaging with his beautifully drawn characters. I got so swept up in it that I forgot this is a vampire horror flick!

Now overt occultism hits. The twins’ young cousin, Sammie (newcomer Miles Caton, a real find), is a badass blues man, and we have been hearing all along how music can be “so true” that “it summons spirits from past and future.” The way Coogler depicts how his performance at the juke joint hits the crowd — and the universe itself — is astonishing. Enrapturing. Spectrally beautiful. It is one of those movie moments that is instantly iconic: so fresh, so different, so perfect that it makes you weep. It will be remembered in the same cinematic breath as slam-bang snippets from The Wizard of Oz and Star Wars. All of Sinners is amazing, but this? It’s one of those scenes that will come to epitomize the enchantment that movies can create.

But Sammie’s music also, alas, fulfills a prediction that his preacher father (Saul Williams: K-pax, One True Thing) has been warning him about: this is the devil’s work, and it can attract evil. And Sammie’s music is what draws the vampires to the juke joint.

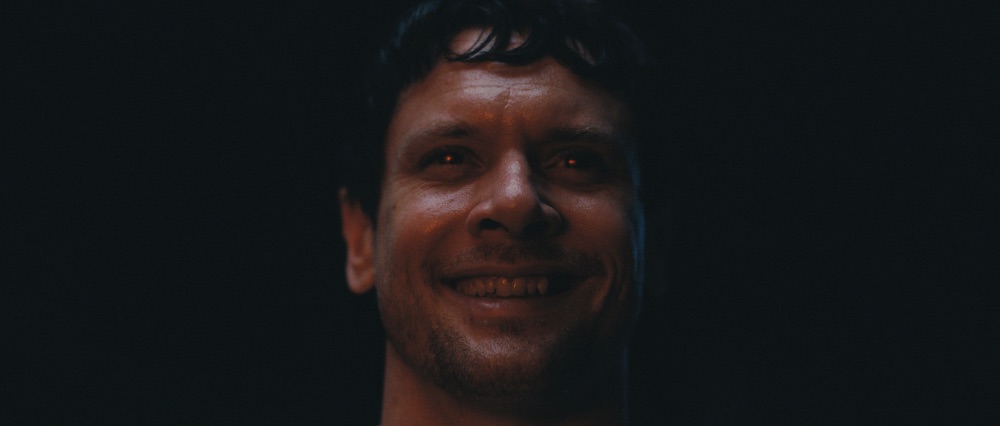

Here is one of the most radical ways in which Coogler innovates with Sinners. Vampires have always been brilliant storytelling monsters for all the varying ways in which they can be metaphoric, but I’ve never seen them used figuratively in this way before: as an analogy for cultural assimilation and appropriation, for resisting it or giving in to it. For these vampires aren’t only white, but the lead vampire, Remmick (the always riveting Jack O’Connell: Back to Black, Seberg), is Irish, and he is clearly very old. He alludes to the English suppression of Ireland and its culture, which began centuries ago, and the weight of his torment suggests that he has been carrying this pain for a long time. And then we have the reality that Irish immigrants in the United States were subjected to horrific discrimination, and still were in the 1930s… until and unless they gave up much of their distinctiveness and assimilated into the mainstream WASP culture. (This was also true of Italian immigrants, which ties into the twins’ experience in Chicago in intriguing ways. Irish and Italian immigrants had to “become” white… which they were able to do in ways not as open to Black Americans.) Remmick here represents that charged possibility for the Black characters: Give up what makes you unique, and you can be accepted by white America. Remmick frames his desire to turn the Smokestack twins and their guests as a good thing, a chance for a better life. (O’Connell is an actor whom I’ve previously accused of being “so very capable of selling both charming psychopathy and wounded innocence,” and he oozes that same seductiveness here.)

Oh, and Remmick just loves their music, too…

I hope that anyone who knows anything about American pop music understands that the roots of that most quintessential of forms, rock ’n’ roll, are blues and jazz and other Black music that white musicians appropriated — stole — without acknowledgement and without recompense from the people who originated these forms. So there’s another thread for Coogler’s tapestry.

On every level, Sinners is a wonder. Costume designer Ruth E. Carter (Black Panther, Keeping Up with the Joneses) ensures that we can tell simply from their clothing which twin ingratiated himself with the Irish mob in Chicago, and which with the Italians. Composer Ludwig Göransson’s (Oppenheimer, Tenet) blues-infused score is electrifying. Jordan’s commanding dual performances are full of subtle distinctions in the brothers’ demeanors, and his entire supporting cast is sublime: Wunmi Mosaku (who killed as a TVA officer in the Marvel series Loki) as Annie, a gentle Hoodoo practitioner and Smoke’s ex; Hailee Steinfeld (Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Bumblebee) as Mary, Stack’s ex, a woman with Black blood (as Steinfeld herself has) who passes for white and isn’t comfortable with how she has a foot in both worlds; Jayme Lawson (How to Blow Up a Pipeline, The Batman) as sultry Pearline, whom Sammie is sweet on; Delroy Lindo (Do You Believe?, Up) as Delta Slim, a blues musician the twins entice to come play at their juke joint; and Yao and Li Jun Li (Ricki and the Flash) as Bo and Grace Chow, a Chinese couple who run separate grocery stores for white and Black customers, and who have their own assimilation story.

Perhaps most delicious of all, Sinners feels like a meta corrective, a deliberate fuck-you to the Hollywood system that sucks up promising young indie directors — as Coogler proved himself with 2013’s simple, brutal social-justice drama Fruitvale Station — and puts them to work on lucrative vanilla blockbuster sequels and other slop, as happened with Coogler. He distinguished himself more than some others with his Creed, a 2015 spinoff from Rocky, and his 2018 Marvel entry Black Panther, films he was able to stamp with his own genuine perspective even inside existing fictional universes. But now he’s done what far too few filmmakers in similar positions to him have managed: he’s extricated himself from the studio spiderweb, at least temporarily (he’s got some more Disney/Marvel stuff in the works), to make a movie that is all his own. Even better, he achieved a massive business and creative win for himself by negotiating with Warner Bros to have the rights to Sinners revert to him in 2050, a concession almost unheard of in the industry. Which means he, not the studio, will be the one making whatever money there is to be made off his work after that point.

Coogler refused to invite those corporate vampires into his world.

more films like this:

• Nope [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV | Peacock US]

• From Dusk Till Dawn [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV | Kanopy US | Paramount+ UK]

Great final line of your review! Good to see that you are writing again!

Yes to both.

Thanks for this! Great review after your time away.

Yes! I was absolutely floored by this scene as I was watching it.

I would advise people watching this to stay through the credits, all the way to the end. Yeah, I know the practice of tacking on mid- and post-credit scenes is eyeroll-inducing by now, but Coogler does it in a way that truly enriches the story instead of just tossing in frivolous scenes or teases for a future film. And (SPOILER-ish?) the fact that he brings in an actual living blues legend to portray an older version of a character is just a real thrill — the cherry on top of a whole film that honors and celebrates the power of the blues.

Oh, the two end-credits scenes are must-sees.

Thanks for the rec! I’m having surgery that will basically leave me homebound most of the summer, and I’m amassing a pile of entertainment for myself. Great to see your name pop up on my feed!

I’m sorry to hear about the surgery but happy to hear about the pile of entertainment. I wish you well with both.

Thank you for the kind words. I am also recovering from surgery, so you have my very heartfelt sympathies.

Sinners has now debuted on premium VOD, so you can watch it at home.