Oh, frabjous film! What a movie. What an experience. Bradley Cooper’s first feature as cowriter and director, 2018’s A Star Is Born, is a marvel: passionate, intoxicating, enrapturing. His second, Maestro, made me feel exactly the same way, though the film itself is radically different. But sitting in the dark, in a big cinema — phone off and put away! — and letting this movie bowl me over? Giving myself wholly over to it? Sheer bliss.

Now, Maestro is a Netflix film, and it’s getting only a limited theatrical release before it debuts on the streaming service on December 20th. I saw it at London Film Festival, on a very big screen with massive sound, in an auditorium packed with cinephiles as eager as I was for it: this was as ardently communal as cinema gets nowadays. But I see a lot of films this way, and it’s still rare for a movie to move me, to rivet and electrify me, like Maestro did. There is something very special going on here, and I fervently hope that feeling will carry over to home viewing. I think it will… if you let it. (Please watch it in the dark with no interruptions, if at all possible.)

The “what has streaming done to movies?” debate will continue. That most people who see a given movie will see it at home has been true since at least the dawn of the VCR, perhaps since the dawn of television. So I wonder if there was something deliberate in Cooper’s creative choices with Maestro, or if they were an accidental side effect of him just trying to do something fresh, that when I think about what an astonishing cinematic high-wire act he has pulled off here, how it feels classic and modern at the same time, what I settle on is that it is as audacious as some early Golden Age Hollywood was — from the advent of sound to the rise of television — when filmmakers were experimenting with visual storytelling and inventing a new language for cinema.

Is it too outrageous to suggest that Cooper is, dare I say it, a new Orson Welles? Am I opening myself up for ridicule with this? So be it. There is a breathtaking boldness, an arrogance, even, at work in Maestro, even more so than with A Star Is Born, which was already bursting with Cooper’s immense confidence as a filmmaker. For sure, there are other filmmakers working today who can legitimately be slapped with the label egotistical, even narcissistic — there’s a reason why the term fauxteur had to be invented — but Cooper gets away with it. Runs away with it. And doesn’t make you — okay, me — hate him for it.

Here’s the thing about Maestro: it is nominally a biopic docudrama. But it doesn’t feel like any biopic docudrama I’ve seen before. I didn’t know much about classical-music composer and orchestral conductor Leonard Bernstein before Maestro, and I didn’t learn many facts about him in this movie, and that’s okay! “It’s not a documentary!” is the usual reminder when some folks complain about omissions or elisions in movie depictions of real people. Cooper and his coscreenwriter Josh Singer (First Man, The Post) have leaned into that, so much so that they’re not even pretending to be documentary-ish. The way they tell the story of Bernstein here is immersive — like, we are there for Bernstein’s professional and personal life in postwar America — but also impressionistic, like, nothing is explained for us, we just let it flow over us.

There’s one brief mention, for instance, of a friend called Jerry… and it was only later that I realized that, oh, that was Jerome Robbins, the director, producer, and choreographer of West Side Story, for which Bernstein wrote the music. Maybe there’s a brief passing mention of Stephen Sondheim, who wrote the lyrics for that production? I can’t really recall. But anyone hoping for a box-ticking exercise in a who’s-who of Bernstein’s collaborators will be disappointed.

Instead, Cooper throws us straight into the deep end: Maestro is, sometimes literally but often figuratively, all rapid-fire party chat at a salon where the smart cultural set is hanging out in the NYC metro area. Maybe that’s 1940s, maybe it’s 1960s. Often the precise conversation eludes us, but we grasp what is going on: vital, energetic life, mostly of an intellectual sort, sometimes somewhat more earthy; there’s a bit of flirtation, a bit of sex, but even they are rooted in brainy creativity.

This is a tale less of one man’s creative output — there’s lots of Bernstein’s music on the soundtrack, but not much diegetic, actually heard in the context of the story being told — and more of what drove him artistically. A lot of that was love of the people around him, including his wife, actress Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan: Suffragette, Far from the Madding Crowd). A lot of it was the love he had to sneak around for: Bernstein was gay, or at least bisexual, and wasn’t very good at pretending he wasn’t, at least not more than he had to publicly in those homophobic days.

And yet this is emphatically not a story that upholds the damaging cultural notion that noble sacrifice in support of a Great Man is a good thing, which these sorts of movies often succumb to. There’s brief moment in which Matt Bomer (Magic Mike’s Last Dance, Papi Chulo) — as musician David Oppenheim, Bernstein’s friend and one-time lover — suddenly realizes that he will never be the center of Bernstein’s life. Not a word is spoken, but the look on Bomer’s face is heartbreaking. But that is nothing next to Felicia’s journey alongside Lenny’s, as she slowly comes to terms with what she has given away of herself in order to be in his thrall. Mulligan’s performance is delicate, seething with sorrow, and yet the film doesn’t dare cast her as a victim, either. The lament here is that the world and all of us in it lose things we aren’t even aware we’ve lost when we try to crush huge spirits like Lenny’s — and like Felicia’s — into tiny boxes.

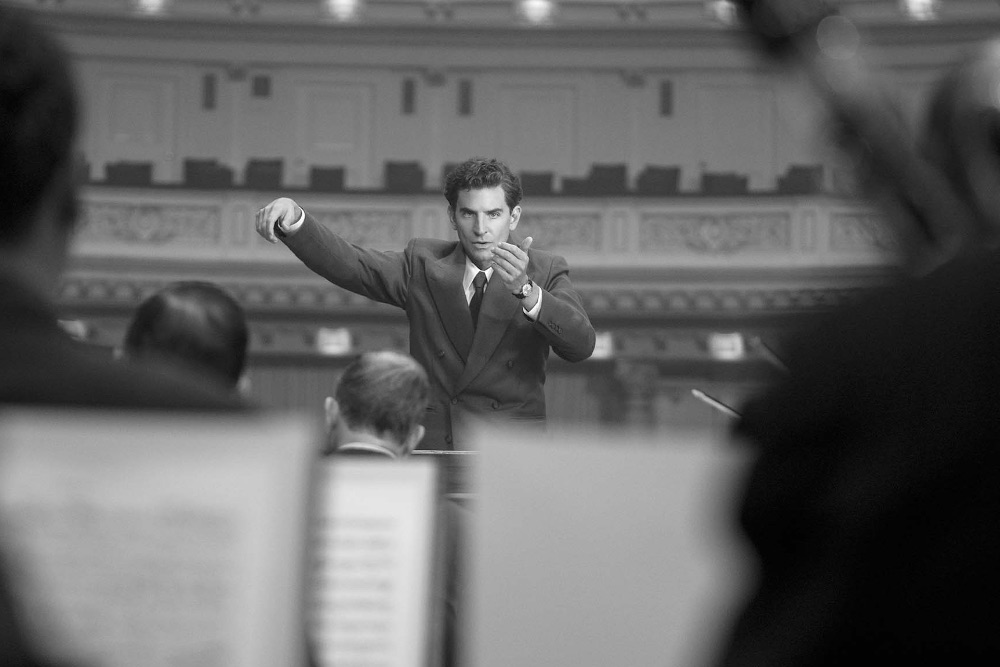

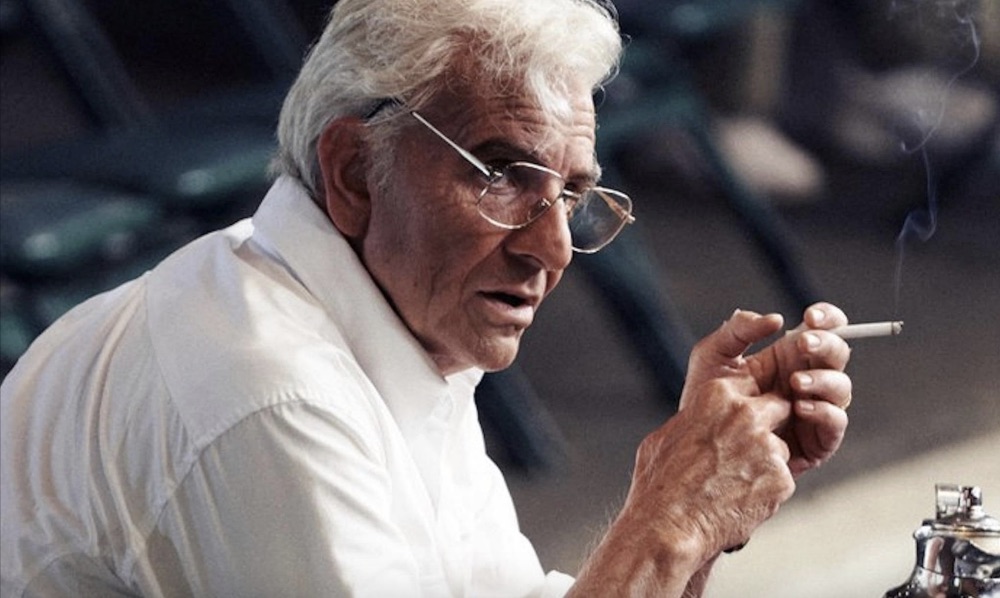

Oh! I haven’t even mentioned that it’s Cooper (Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, Avengers: Endgame) portraying Bernstein, and he is sublime. A kerfuffle ensued a few months ago when the first photos of Cooper as Bernstein were released and showed him wearing a prosthetic nose that some characterized as “Jewface”; Bernstein was Jewish, and Cooper is not (though his own nose is pretty impressive!). This didn’t seem unfair at the time — the fake nose initially did come across as almost unnecessary — but in the context of the film itself, it works. Nose notwithstanding, Cooper utterly disappears into the role to the point where he’s often unrecognizable, not just physically but deep-down soulfully. He seems to have taken onboard Bernstein’s unflappable confidence, and it is a delight to watch. There’s an bewitching scene late in the film in which Cooper-as-Bernstein conducts a concert in a cathedral: it roils with passion and joy, and soars like the music itself. Perhaps no single other element of the film sings as much with Bernstein’s — and Cooper’s — power.

I’m not fluent in music-talk, but I feel like Bernstein’s compositions are eclectic, staccato, genre-defying, full of unexpected tonal shifts that nevertheless work. Maestro echoes its subject’s music. There’s a visual and narrative freshness to this movie, a wonderful eccentricity, a delicious audacity. They’re all a kick in the pants to a mainstream cinema that has, in many ways, been feeling more and more moribund. I think this is a perfect movie, but I would also hope that those who don’t agree would at least recognize that it pushes boundaries in a way that we very much need right now.

more films like this:

• First Man [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV US | Apple TV UK]

• A Star Is Born [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV]

So it looks to me like I’ll be staying with the Oscars to the end because that’s where they put Best Actor and Best Director.

I long to be as under the spell of this film as you were, because the cinematic experience you describe is the entire point of going, to be enthralled like this. I’m so looking forward to seeing it!